Remember last summer when the media attempted to parse the arguments and meaning of the Supreme Court's sessions on the Affordable Care Act? Wasn't it fun to play the "How will they vote" game? Wasn't it extra fun when Justice Roberts played that big bad joke on Antonin Scalia and sided with the squirrely liberals? Well, if you liked that, then you have to love last week's arguments in the case surrounding the constitutionality of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965. Here is one of the iconic laws of the civil rights era under siege from a hostile conservative majority, with the possible (probable) result that it could be overturned. But really, what's the case all about? And what's the fuss about comments from Justices Scalia and Roberts? if these questions burn in your soul, then you've come to the right place.

Here's the recap for your edification and delight.

The Supreme Court will rule on whether a key part of the Voting Rights Act, Section 5, should stand. The background on Section 5 can be found

here, but the basic idea is this:

Section 5 freezes election practices or

procedures in certain states until the new procedures have been subjected to review, either

after an administrative review by the United States Attorney General, or after a lawsuit before

the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. This means that

voting changes in covered jurisdictions may

not be used until that review has been obtained.

Application of this formula resulted in the following states becoming,

in their entirety,

"covered jurisdictions": Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana,

Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia, In addition, certain

political subdivisions (usually counties) in four other states (Arizona,

Hawaii, Idaho, and North Carolina were covered. It also provided a

procedure to terminate this coverage.

Under Section 5, any change with respect to voting in a covered jurisdiction -- or

any political subunit within it -- cannot legally be enforced unless and until the

jurisdiction first obtains the requisite determination by the

United States District Court for the District of Columbia or makes a submission to the

Attorney General. This requires proof that the proposed voting change does not deny or

abridge the right to vote on account of race, color, or membership in a language minority group.

If the jurisdiction is unable to prove the absence of such discrimination, the District Court

denies the requested judgment, or in the case of administrative submissions, the Attorney

General objects to the change, and it remains legally unenforceable.

What this means is that none of the states listed above can make a change to its voting laws or procedures (changing polling places, hours, method of voting, and so on) without the blessing of the Justice Department. During the 1960s, when the law was passed, many states severely restricted African-American voting rights. The argument today is that almost 50 years later, those restrictions are unnecessary and burdensome.

But there's also a section of the case that has to do with Section 2,

as discussed in this article.

The legal issue turns on two main parts of the act: Section Five, which

covers jurisdictions with a history of discrimination, and Section Two,

which covers the entire country. Both sections outlaw rules that

intentionally discriminate against or otherwise disproportionately harm

minority voters. Section Two would remain in effect even if the court

strikes down Section Five.

But reliance only on Section Two would mean a crucial difference in how

hard it may be to block a change in voting rules in an area that is

currently covered by Section Five. Those jurisdictions, because of their

history of discrimination, must prove that any proposed change would

not make minority voters worse off.

By contrast, under Section Two, the burden of proof is on a plaintiff to

demonstrate in court that a change would prevent minorities from having

a fair opportunity to elect representatives of their choice.

“Getting rid of Section Five is not getting rid of voting rights; it

would just make voting rights litigation look like normal lawsuits,”

said Ilya Shapiro, a legal scholar at the Cato Institute, which filed a friend-of-the-court brief

urging the court to strike down Section Five. “It would mean that if

the federal government claims people have been harmed, it would have to

prove it.”

But J. Gerald Hebert, who

formerly handled voting rights litigation for the Justice Department and

is now in private practice, said that losing Section Five would be

“devastating to protecting voting rights” because the costs of a lawsuit

are so steep. Jon Greenbaum, the legal director for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

said it would mean that the bulk of changes that now receive automatic

scrutiny by the federal government could take effect without any review,

eliminating a deterrent against mischief.

In other words, under Section Five, the burden of proof is on the municipality to prove that it's not discriminating by passing a law that affects voting. Under Section Two, the burden of proof is on the plaintiff, and they would have to foot the bill for the lawsuit. Getting rid of Section Five doesn't mean that states can pass discriminatory laws because Section Two, which covers the whole country, would still be in effect. But like most conservative ideas, the economic and legal toll would be on those who are most likely to be affected, who are also the least likely to able to pay to defend their rights.

The case before the court comes from Shelby County, Alabama. Congress routinely re-approved the Voting Rights Act in 1970, 1975, 1982, and in 2006 extended it for 25 years.

From NBC News,

Shelby County’s lawyer Bert Rein argued that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act – which Congress renewed for another 25 years in 2006 – is unconstitutional because the formula used to determine which states are covered is outdated – based on voter turnout and registration data from 1972.

In essence, Shelby County is saying that the law is outdated, is based on obsolete information, and no longer reflects modern southern (and other) politics.

The other side of the argument is that the Voting Rights Act is working, so why get rid of it?

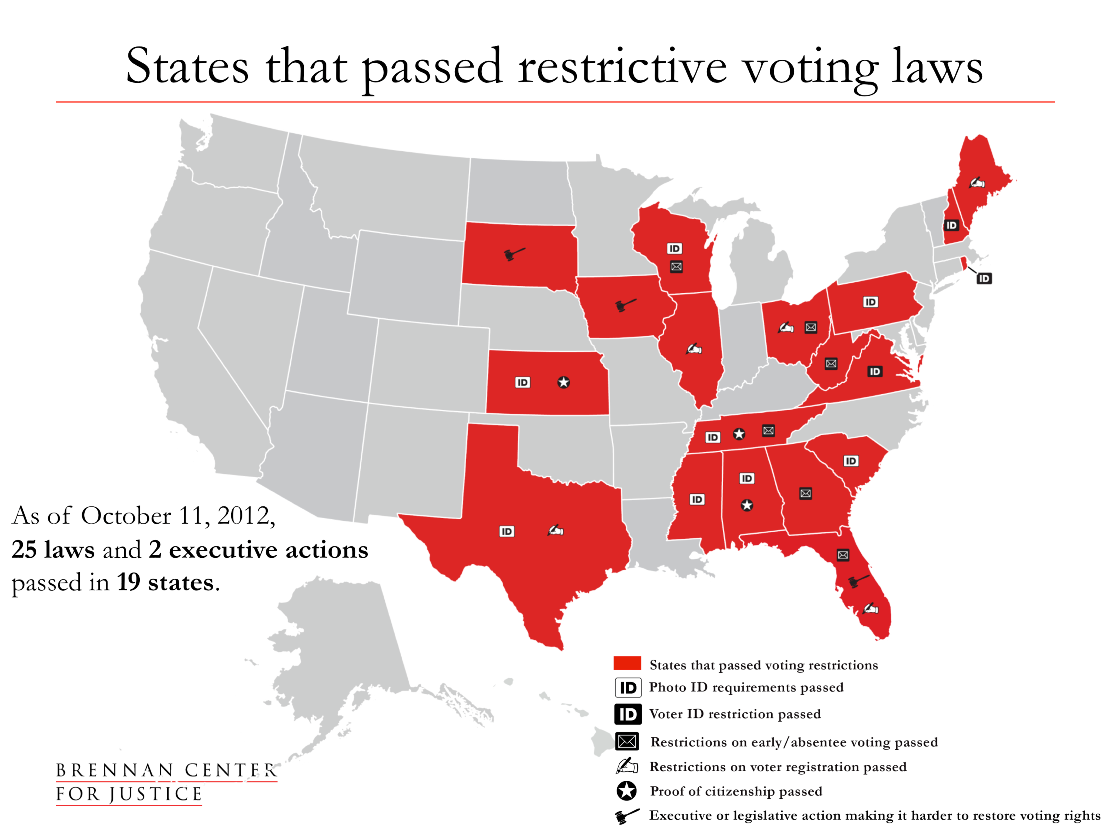

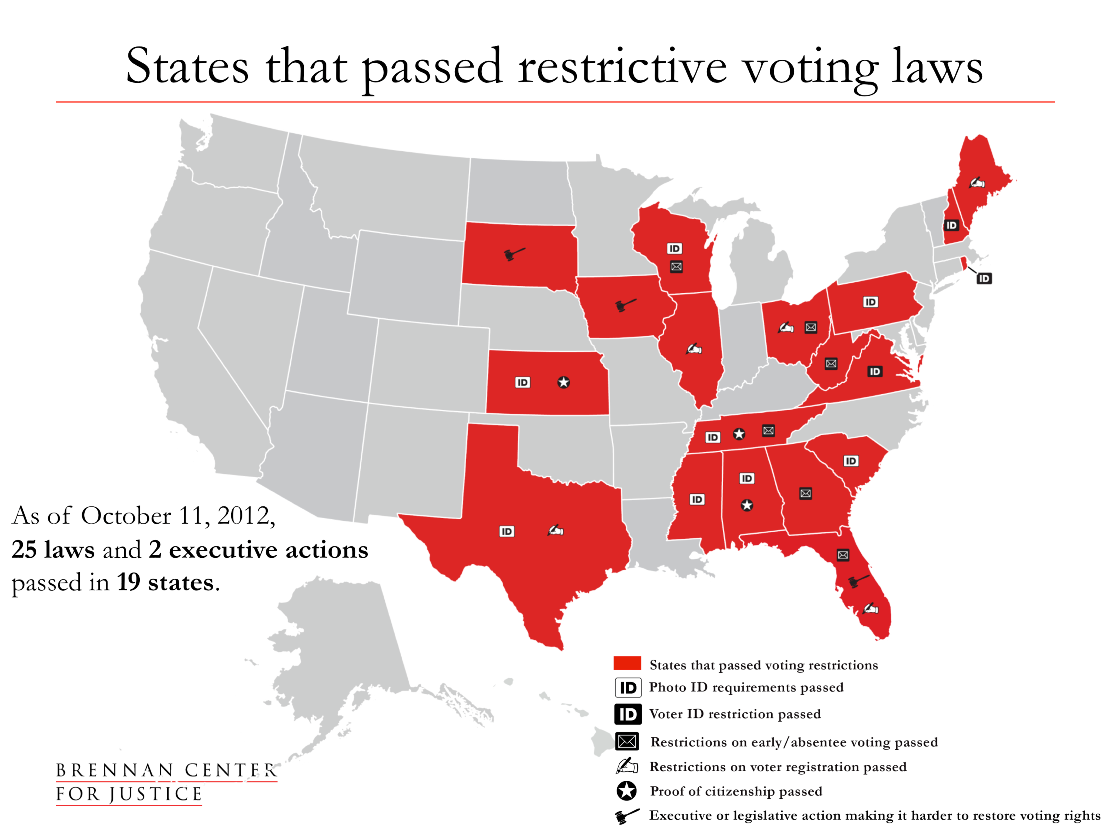

There is a plethora of data that shows that the law is still needed, and that taking federal oversight away from places that have histories of discrimination is an invitation to continued mischief. This chart below graphically illustrates the effects of such laws.

As you can see, states that can do as they please on voting laws, and only have to worry about deep-pocketed plaintiffs challenging them on Section Two, have passed the most restictve voting laws. If the Supreme Court strikes down the Act, it could lead to more Voter ID laws and the suppression of early voting laws that seem to help minority voters in the states that have them. Remember that it's not just the south anymore.

Laws that dissuade voters from voting is a national problem.

It shouldn't surprise anyone that during oral arguments, the conservative members of the court seemed to side with Shelby County, saying that the law was outdated and, in Justice Scalia's words,

"very likely attributable, to a phenomenon that is called perpetuation of racial entitlement. It's been written about. Whenever a society adopts racial entitlements, it is very difficult to get out of them through the normal political processes.”

Racial entitlement.

There's a reason that there was loud backlash against Scalia for uttering this phrase. Before there was a Voting Rights Act, wasn't the entitlement on the side of whites? And wasn't the remedy to make sure that all people could exercise their rights? How then did the remedy become an entitlement for African and Native Americans? All these people were asking for was the franchise. Now Justice Scalia is reclassifying them as a group that doesn't deserve any more protections.

Further,

Chief Justice Roberts went so far as to compare African-American voting patterns in Mississippi, which he said had the best ratio of black turnout to white, to Massachusetts, which he said had the worst ratio. Not only

was he wrong on the facts, but does anyone truly believe that Mississippi had, and has, a better record when it comes to open voting than the Bay State?

Massachusetts Secretary of State William Galvin:

“He’s wrong, and in fact what’s truly disturbing is not just the

doctrinaire way he presented by the assertion, but when we went

searching for an data that could substantiate what he was saying, the

only thing we could find was a census survey pulled from 2010 … which

speaks of noncitizen blacks,” Galvin said. “We have an immigrant

population of black folks and many other folks. Mississippi has no

noncitizen blacks, so to reach his conclusion, you have to rely on

clearly flawed information.”

By contrast, Justice Breyer referred to voting procedures as a disease, saying,

“It's an old disease, it's gotten a lot better,

a lot better, but it's still there,” he said. “So if you had a remedy

that really helped it work, but it (discrimination) wasn't totally over,

wouldn't you keep that remedy?”

Well, yes, but apparently, he's in the minority.

Although it looks rather grim for keeping the Voting Rights Act intact, please do remember that it looked similar for the fate of the Affordable Care Act this time last year and we know how that worked out. Perhaps Justice Roberts or Kennedy, who also seemed hostile to upholding the Act, will change their tunes in chambers, but I don't expect it. Given that both Florida and Ohio had significant problems with their voting procedures, and also given the love that many Republican Governors have for placing roadblocks to voting for minority communities, I could see an expansion of restrictions from the south to other parts of the country. It would then be up to individual voters to bring suits, but again, they would also have to pay for them.

One of the popular phrases that opponents of the Act use is that we've elected an African-American President twice, proving that we've turned the corner on race and voting. Very true. But the other side of the coin is that we've made history not only because of progress, but in spite of state laws aimed at disenfranchising minority voters who stayed in line well past poll closing time and used social media to publicize their plight. When we no longer have to worry about these shenanigans, then we won't need the Voting Rights Act anymore. But until then, it's clear that we still do.

For more, go to www.facebook.com/WhereDemocracyLives and on Twitter @rigrundfest